Part 16 in a series of 18 discussion papers

The remaining time to change course and fully avoid the rise of surface temperature to levels above 1.5°C is now tragically exhausted. Our governments have deceived us. Even if the most rapid emissions reductions measures are fully implemented over the next seven years by all countries, those measures will probably be unable to avoid us witnessing warming exceed the 1.5°C limit.

It was not until December 2015, when the Paris Agreement was negotiated, that countries, including Canada, agreed “to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C.” Recognizing that the newly stated 1.5°C goal would require much deeper and faster changes in energy policy, the parties to the Paris Agreement in 2015 requested that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) prepare a Special Report on the impacts of warming to 1.5°C and on the measures needed to meet that goal. Three years later, on October 7, 2018, the IPCC Special Report on Global Warming to 1.5°C was published. It provided the results of comprehensive research about the magnitude of the emissions reductions that would be required to keep the warming increase to 1.5°C.

One core finding reported in the Special Report was that all releases of CO2 into the atmosphere must reach “net-zero” by 2050 to give us a 66% chance of reaching the 1.5°C goal. “Net-zero” means that, beyond 2050, no additional CO2 can be safely added to the cumulative amount of CO2 that, by then, will already have been released into the atmosphere.

A second core finding, based on the scientific evidence set out in detail in that report, was that to give us a realistic chance to achieve the goal of net-zero by 2050, the annual level of global emissions must be reduced 50% below the 2019 level by 2030. That conclusion about the massive scale of the emissions reductions required by 2030 (stated in terms of a 45% reduction below the level of global emissions in 2010) was clearly stated in the Summary for Policy Makers which formed part of the report released on October 8, 2018. The representatives of the Government of Canada explicitly approved the text of the Summary for Policy Makers.

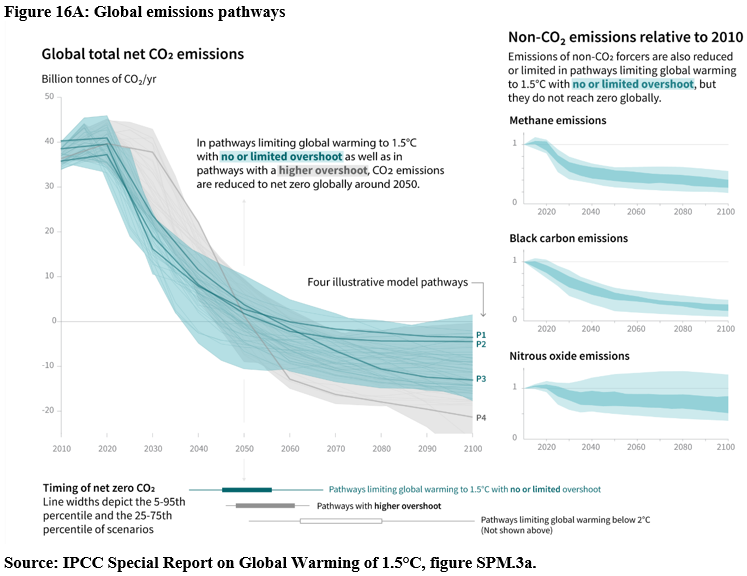

The IPCC Special Report released in October 2018 also revealed that the impacts of warming as it rises above the 1.5°C threshold will be very much worse than previously known, and that in the case of some parts of the climate system and ecosystems (the destruction of coral reefs and marine life, the melting of glaciers and ice sheets, sea level rise) the losses will be catastrophic. The report dispelled any notion that limiting the increase in the earth’s average surface temperature to 2°C would be a “safe” or “acceptable” goal. The urgency and the stringency of the deep cuts in overall global emissions required by 2030 is depicted in Figure 16A below, which is reproduced from figure SPM.3a published in the Summary for Policy Makers document.

The total annual level of global emissions is given on the vertical axis of the graph, measured in billions of tonnes of carbon dioxide per year (GtCO2). The global total shown for 2020 is a little over 40 GtCO2. Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions are represented on the main graph on the left. CO2 accounts for most human caused GHG emissions, more than 80% of that total. The other 20% of human caused emissions are comprised of methane and other GHGs, shown on the right of Figure 16A.

Four mitigation pathways are highlighted, identified as P.1, P.2, P.3. and P.4. Each offered a different combination of energy policy, technologies, and land use strategies to achieve the hoped-for “net-zero” outcome by 2050. Importantly, each of the depicted pathways relied on deploying Carbon Dioxide Removal methods (CDR) to some degree.

P.1 is described in the report as a mitigation plan aimed to reach “net-zero” by 2050 with minimal reliance on CDR technology. The Summary Report says this about the P.1 pathway: “Afforestation is the only CDR considered; neither fossil fuels with CCS nor BECCS are used”.

Under P.1, CO2 emissions would begin to rapidly decline from a little over 40 GtCO2 in 2020 down to about 20 GtCO2. by 2030.

But that decline, which was supposed to begin in 2020, has not occurred. In 2019, the annual level of global emissions reached a new peak. Emissions dropped significantly during 2020 due to the economic impact of COVID-19 but resumed their growth again in 2021 and in 2022.

The IPCC Special Report in 2018 report was clear that if we fail to meet the 2030 target, or choose not to, our last resort will be to attempt later to use CDR technologies on a very large scale to remove the accumulated “residual emissions” from the atmosphere.

Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) technology

The Special Report concluded that to “return global warming” to less than 1.5°C it will be necessary in future to deploy CDR technologies on a substantial scale to “compensate” by removing CO2 from the atmosphere.

All pathways that limit global warming to 1.5°C with limited or no overshoot project the use of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) on the order of 100–1000 GtCO2 over the 21st century. CDR would be used to compensate for residual emissions and, in most cases, to achieve net negative emissions to return global warming to 1.5°C following a peak (high confidence). CDR deployment of several hundreds of GtCO2 is subject to multiple feasibility and sustainability constraints (high confidence). Significant near-term emissions reductions and measures and lower energy and land demand can limit CDR deployment to a few hundred GtCO2 without reliance on bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) (high confidence).

— Summary for Policymakers, IPCC Special Report 2018, page 19 (emphasis added)

In the case of these scenarios, the problem of “residual emissions” (also referred to as “overshoot”), namely the amount of excess CO2 released into the atmosphere over the next forty years that will take us well above the 1.5°C limit, would have to be solved, if it can be solved, by the development of Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) technologies.

The scale of future carbon dioxide removals proposed in several of these scenarios is enormous. Pathways P.3 and P.4 envision that, by 2050, and thereafter, we must be removing about 10 GtCO2 and as much as 20 GtCO2 every year from the atmosphere and continue doing so for four or five decades after that. To put those numbers into perspective, at present we are releasing annually an additional approximate 42 billion tonnes (Gt) of CO2 into the atmosphere, of which the vast majority (about 37 billion tonnes annually) is from burning oil, coal, and natural gas. The magnitude of the future removals that would be required under these schemes is enormous.

The report states that the viability of these schemes is “subject to multiple feasibility and sustainability constraints”. That is a bureaucratic way of saying that the viability of these proposed solutions based on CDR technologies is unknown and completely conjectural. At present, the required CDR technologies either do not yet exist at all, or in some cases they exist only in very small-scale experimental projects. We have no assurance that these schemes will be viable on the vast scale envisioned.

One prominent CDR scheme, called Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECSS), envisions that we will grow crops on a massive scale that will absorb CO2 from the air in the growing season. These crops will then be harvested and burned, and through that burning process the CO2 embedded in the plants will be released and captured by CCS, then compressed and injected underground for permanent storage. Vast planting areas of land would be needed to grow the required biomass, which would significantly impact on the limited croplands available for the world’s food supply.

The entire BECSS process would itself be energy-intensive and would add enormously to our future energy needs – and would impose enormous economic costs and social burdens on our children and following generations. It would require allocating a substantial share of the world’s available croplands (and water resources) to grow adequate plant material and trees that would be burned in these future CCS facilities to extract their CO2. Hence the report’s warning about “sustainability constraints”.

Other proposed CDR technologies, still at the concept stage, envision chemical processes and materials (e.g., silicate rocks and seaweed cultivation) that would directly absorb CO2 out of the air. There are experimental prototypes of some of these ideas. Huge unanswered questions remain about the viability of scaling up these schemes, energy use, and cost. Other than very small-scale experimental prototypes, direct air removal technology does not exist.

The situation now in 2023: the implications of “overshoot”

Since the warning given five years ago by the IPCC Special Report, additional reports by the IPCC and by others have documented the ongoing failure of emitting countries even to begin to implement policies that will achieve any significant reduction of global emissions by 2030.

The IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report (ARC) was published in three parts through 2021 and 2022, culminating with the Synthesis Report released on March 20, 2023. Also, a series of annual UN Emissions Gap Reports (most recently the UN Emissions Gap Report 2022, released on October 27, 2022), track the still rising path of global emissions and provide updated projections to 2030.

Global average surface temperature is now already around 1.1°C above the pre-industrial level. The most recent reports confirm that global emissions would have to be cut 43% below the 2019 level by 2030 to give us a 50% chance to keep the warming increase within the 1.5°C threshold.

Sadly, even with the full and successful implementation of all existing new emissions reductions policies promised by all countries (including by Canada which promises a 40% reduction of its domestic emissions by 2030), global emissions are currently on track to continue increasing to 55 GtCO2eq by 2030. (They reached an estimated 52.8 GtCO2eq in 2021). The existing commitments by countries to rapidly cut their own national emissions by 2030 (referred to as their “Nationally Determined Contributions” or “NDCs”) offer only a small fraction of the total reductions needed.

The annual level of global emissions by 2030 will still be higher than it was in 2019, even if all the NDCs promised so far are fully achieved. That higher level of global emissions by 2030 will put us on a pathway to a temperature increase of 2.6°C above pre-industrial levels.

Further, the remaining time to change course and fully avoid the rise of surface temperature to levels above 1.5°C is now tragically exhausted. The following statement taken from the IPCC’s most recent report explains the extremity of our predicament:

Global warming is more likely than not to reach 1.5°C between 2021 and 2040 even under the very low GHG emissions scenarios (SSP1-1.9), and likely or very likely to exceed 1.5°C under higher emissions scenarios.

— Synthesis Report of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, Longer Report, section 4.1

That means even if the most rapid emissions reductions measures are now adopted and fully implemented over the next seven years by all countries, those measures will probably be unable to avoid us witnessing warming exceed the 1.5°C limit.

Once average surface warming exceeds 1.5°C, even by one-tenth of a degree to 1.6 or to 1.7°C, the scale of the emissions “removals” that would be required in future to roll us back to a more survivable level of warming using any of the envisioned future (but presently non-existent) CDR technologies is enormous. The volume of required reductions can be calculated, but the number is so vast it is a measure of fantasy and delusion:

Reducing global temperature by removing CO2 would require net-negative emissions of 220 GtCO2 (best estimate, with a likely range of 160-370 GtCO2) for every tenth of a degree (medium confidence).

— Synthesis Report of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, Longer Report, section 3.3.4

To roll back warming by just one-tenth of a degree Celsius we would need to “remove” from the atmosphere about 220 GtCO2, which at current rates of burning coal, oil, and natural gas is equivalent to about five years’ worth of accumulated emissions. Faced with this horrific future, Government Ministers and Members of Parliament continue to approve and enable the ongoing expansion of Canada’s oil production for another 10 or 20 years, while they talk endlessly about carbon capture and storage technology, about underground storage of carbon, direct air removal, and “negative emissions”.